In the broadest possible terms, Jungian psychology divides the self into three parts, much like Freud does, but Jung’s divisions have less to do with urges than they do with perception. There is the self we are, the self we believe ourselves to be, and the self perceived by others. With sufficient observation and self-awareness, it’s possible to discern how others perceive us and even alter that perception. Naturally, it’s something we can apply to our characters as much as ourselves.

“William Wallace is seven feet tall!”

“Yes, I’ve heard! Kills men by the hundreds, and if he were here he’d consume the English with fireballs from his eyes and bolts o’ lightning from his arse!”

Heroes, protagonists and so-called ‘good guys’ rarely pay much attention to how they’re perceived. We accept and, on some level, expect a level of humility from most heroes that precludes them from worrying about what others think overmuch. Occasionally, you’ll have somebody like Tony Stark, who uses the media’s perception of his persona not only to call attention to the evils he fights against but also to obfuscate the true depth of his character.

For the most part, though, our heroes tend to be more like John McClain or Aragorn, avoiding undue attention as much as possible so they can focus on the task at hand. The perceptions others have of them grow of their own accord, and things that they do in the pursuit of their goal become legendary tales to those who hear of their feats. It’s how the humble policeman and the reluctant ranger become heroes and kings.

“The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.”

Villains, on the other hand, make use of their perceptions often. Most of the time, it’s in the course of playing up their menace. The more scared you are of someone, the less likely you are to stand up to them. Some of them go beyond mere intimdation to craft a perception of themselves in the minds of others so powerful that they don’t need to look, say or do anything out of the ordinary.

Sure, messing with Megatron or Skeletor is a bad idea. You don’t assume, however, that picking on the little guy in the running crew could land you in big trouble. Many true villains cultivate perceptions of quiet, introverted advisors even as they steer the course of the world around them through quiet manipulation.

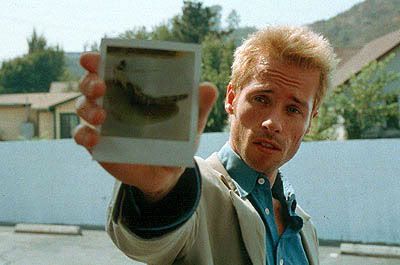

“So… I’m chasing this guy. Wait… wait, no, he’s chasing me.”

Finally there are those with conditions that might color the perception of others regardless of any moral stance they have. When they become aware of these perceptions, and the expectations that can come along with them, they can be just as manipulative of those perceptions as the canniest, most insidious villain. It causes other characters to question what they know and how they’ve come to know it.

“The dwarf’s a major threat? The psychopathic murder’s polite and cultured? The apologetic man with the short-term memory loss has ice water for blood?”

And let us not forget the perceptions of the audience. A character might seem to be utterly irredeemable in their eyes, until you allow them into that character’s point of view or expand upon their background. Let the audience spend time with them, fill in some of the blanks they might have populated with their preconceptions, and watch their perceptions change. When it happens, the audience will often take a moment to realize and appreciate the shift, then proceed to seek more story. And we, as storytellers, should not hesitate to oblige.

Leave a Reply