This week, Chuck invited folks like me to write on one of my favorite sci-fi subjects: time travel.

The office was everything one could want from upper-crust living. He sat behind a wide desk as he monitored the incoming streams of data from various sources on the screen. That was really a secondary concern, however. Mostly his attention was on the antique clock on his desk.

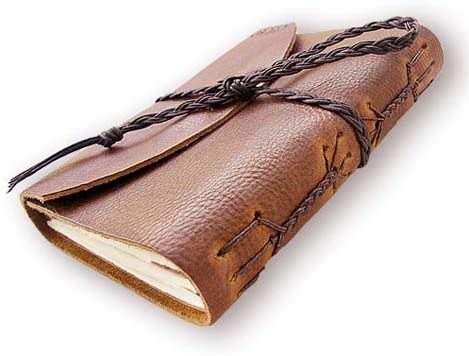

He turned the key in the top drawer of the desk, opened it, and pulled out the journal within. It was bound in leather, the pages yellowing at the edges, and filled the office with a musty, ancient smell. And yet, for its obvious age, it was amazingly well preserved. He opened it to the page marked with a dark ribbon, produced a fountain pen, and wrote down the current date and time. He recorded his current savings account information, the name he’d taken, the degree he’d pursued, and the occupation he used. Finally, after a moment’s pause, he wrote a single name.

The same name appeared on his planner for a meeting in twenty minutes.

He closed the journal and put it in a static-free bag designed for long-term preservation. Any contents of the bag were extremely resilient against the passage of time. Already, he was thinking of the seemingly abandoned tower in England’s countryside, a crumbling edifice of stone along the Prime Meridian, once used as an observatory by druids. They’d known of the place’s power, even if they never fully utilized it.

The journal spoke of the first trip to the tower. In fact, it contained a few entries from before the tower had been built. Transportation was a great deal easier now than it had been back then. Some of the entries in the journal were simple, one-line mentions of a name and a destination. He got a chill when he thought of some of those sojourns. But the alternative was far more horrifying to contemplate.

He put the journal aside and consulted his map of the building again. After the meeting he would leave the room, walk briskly (but not too quickly) down the hall, take the stairs down, hail a cab, and be on a plane to England inside of an hour. A passport in one of the previous names he’d used had been renewed and would allow him to effectively disappear. It was a solid plan, and he had confidence in it, but he looked at the journal again and felt a stab of fear.

Nobody who found it would understand. It would seem like madness. The significance of the names within would be baffling and obfuscatory. Why weren’t the names of anyone famous in there? They wouldn’t know. But he’d learned all too well that it was those who stayed out of the limelight who shaped the course of the future.

Before destinations, account numbers, or any other information, the journal always contained a statement on how things were at home. The world’s population, the state of its powers, how close things were to collapse, the amount of pollution in the sky. With every new entry, things got a little better. The future was improving, bit by bit. He was making it happen.

And he would continue to do so.

He knew that, no matter what, in – what, a hundred and fifty years, now? – he and his colleagues would find the journal, develop the technology described within, and find the next focal point of change in the world. Political movements, men poised to engineer disaster, overzealous crusades… it was difficult, at times, to determine exactly when and whom to target. And once the time and place and target were chosen, there was no going back.

The man now being shown to the conference room had been married twice, supported one child from a previous marriage, and lived with his current wife and three other children. He knew that sympathy for this one man and his family meant the doom of billions. The tragedies in his past needed to become the formless, unwritten future. He thought of the journal, of the atrocities mentioned that never came to pass because of him.

Or rather, because of where and when he’d decided to go, or would decide to go, in a hundred and fifty years.

He took some painkillers. This always made his head hurt. He focused on the mission, his escape plan. He opened the briefcase, putting the journal next to the stacks of cash he’d collected over the past two months. The savings account that would survive was three names away. Static-free bags in the tower had several lives’ identification, an easy matter to renew. He closed the briefcase, stood, and walked towards the conference room.

Waiting for him was someone concerned solely with profits and income. The meeting was supposed to be about stocks and commodity futures. After this, the profiteer would use his money to fuel a political campaign based on fear-mongering and blatant disregard for the middle class, which would lead to a world-wide economic collapse as the underclasses imploded and the upper class fell, having nobody to support them.

He shook the profiteer’s hand, waited for him to sit, and opened his briefcase.

He produced the pistol without saying a word. The profiteer raised his hands in surrender. He was unarmed. He was about to say something.

The silencer muffled the gunshot. And the Mozambique Drill that followed.

His ears ringing, he placed the handgun beside the body. He closed his briefcase, turned away from the scene, and left the room.

He had taken the stairs many nights before, timing himself with each run. He rounded the corner at the base of the stairs to find the profiteer had brought his own security. He turned to run, hearing the gunshots but not really feeling them until he was a block away.

As he fell, he noticed movement by his side, someone taking the briefcase. He looked up. The figure drew a pistol, fired back at the security, and looked down.

He was looking at his own face.

…At least the journal’s safe…

Leave a Reply