{no audio this week – sorry for the inconvenience!}

Many authors have speculated that we as a species are walking a knife’s edge between transcending our previous limitations in terms of body, mind, and spirit, and falling into an inevitable downward spiral of self-destruction we’re simply too lazy to avert. It’s a resonant message and especially popular in the genre of cyberpunk, where near-future technology that pushes the envelope of human potential is often juxtaposed with the plight of have-nots struggling to keep up with the haves. Films like Blade Runner, books like Snow Crash and games like Deus Ex: Human Revolution drive these points home in stunning ways, and to that list I would add the 1988 Japanese animated feature Akira.

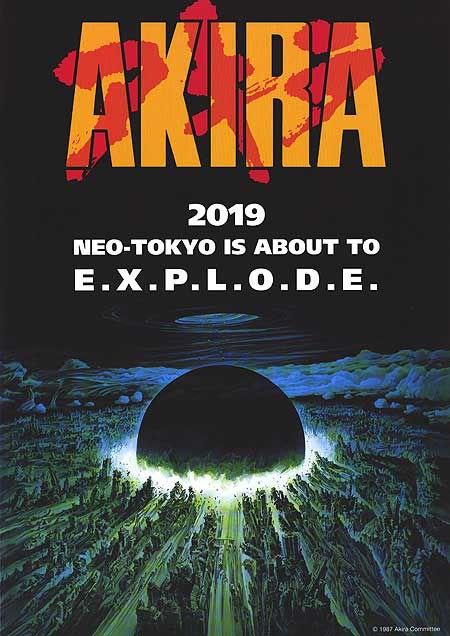

The year is 2019. Tokyo, having suffered major losses during a cataclysmic event in 1988, has been rebuilt as Neo-Tokyo. Violence is breaking out on its streets between rival biker gangs the Clowns and the Capsules, the latter lead by a young upstart named Kaneda. His friend, Tetsuo, nearly runs over a small child in the course of a fight, but the child turns out to be a psychic, the result of experimentation by the military in the wake of Tokyo’s destruction. Tetsuo, in turn, is discovered to possess a great deal of psychic potential himself and is taken for testing. While Kaneda hooks up with an underground dissident movement to help his friend, the military moves to stop the experiments on Tetsuo by killing the boy, lest he realize his potential which mirrors that of the child who destroyed Tokyo in the first place, the child named Akira.

Like many works of its type, Akira began life as a manga in the 1980s. Rather than hand the 2000-page magnum opus to someone else, the production team ensured that the author, Katsuhiro Otomo, wrote and directed the film adaptation. The result was something new for the art houses of anime. Notorious for cutting corners and running out of money before production was complete (look no further than Neon Genesis Evangelion as evidence of this), Akira boasted not only a robust budget but fully lip-synced dialog and animation as fluid as possible, resulting in a film that holds up in terms of both style and substance over 20 years later.

Didn’t Edna Mode say something about capes?

With golden pixels each costing the price of a meal flying around in modern productions, seeing hand-drawn animation this detailed and imaginative is incredibly refreshing. Watching Akira unfold, either for the first time or on repeated viewings, makes the skill and dedication of the artists at work obvious without them needing to impose themselves upon the work. Even when the film delves into its more symbolic and psychological elements, the crux of the film remains the narrative and the characters, allowing the theme and mood to speak for themselves rather than making them overt elements in the storytelling. I know a few auteurs who could take notes from this kind of film-making.

A large part of Akira‘s success is due to the characters being fully realized individuals, not just cyphers. Kaneda and Tetsuo clearly have a strong bond, even if the gang leader picks on the smallest member of his crew quite a bit. It’s realistic dialog that conveys a great deal of emotion and history without needing to dive into overlong exposition or diatribes on feelings. The stoic, pragmatic Colonel at the heart of the experiments that unlock Tetsuo’s powers may seem one-dimensional at first, but his relationship with the test subjects and utter contempt for government corruption quickly deepen and expand his character. Even minor roles, like the dissidents and other members of the Capsules, have a force of personality that helps Akira proceed in a very natural and straightforward manner, even towards the end when psychic powers start going incredibly haywire.

You wish your ride was this sweet.

There’s been talk of a live-action adaptation of Akira since Warner Brothers acquired the rights in 2002, with the typical rumors of casting flying around even as it waffles between in-production and shut down. Personally, I don’t know how one could pull off an effective adaptation of Akira in the United States. A big part of Akira‘s success is its haunting callback to being the victims of nuclear assault and needing to rebuild in the wake of terrible cataclysms. While there’s a lot of interest in the States in terms of cyberpunk, civil unrest, delinquent youths, and the nature of corruption and maturity, we would approach these things from an entirely different perspective and I think Akira would suffer for that. The film as it is tackles each of these themes within its running time without feeling dull or overly preachy. It presents human nature, terrifying and limitless and raw and wonderful all at once, as it is and as it could be.

Given that the film is so thoroughly Japanese, from its themes to its soundtrack to its setting and culture, I would recommend watching Akira in that language with subtitles. Many nuances of the language can get left behind even by the most skilled dub artists, and there’s also the fact the film was re-dubbed in 2001 which inevitably can lead to arguments over which version is best. Regardless of how you watch it or in what language, however, Akira is undoubtedly worth your time. It’s a superb blend of action, intrigue, and young existential angst, all conveyed with some of the finest hand-drawn animation you’ll ever see. Over two decades after its release, it still holds up. After all, where else will you find a movie that, without skipping a beat, contains magnetically-driven motorcycles, freaky child psychics, space lasers and the true meaning of friendship?

Josh Loomis can’t always make it to the local megaplex, and thus must turn to alternative forms of cinematic entertainment. There might not be overpriced soda pop & over-buttered popcorn, and it’s unclear if this week’s film came in the mail or was delivered via the dark & mysterious tubes of the Internet. Only one thing is certain… IT CAME FROM NETFLIX.