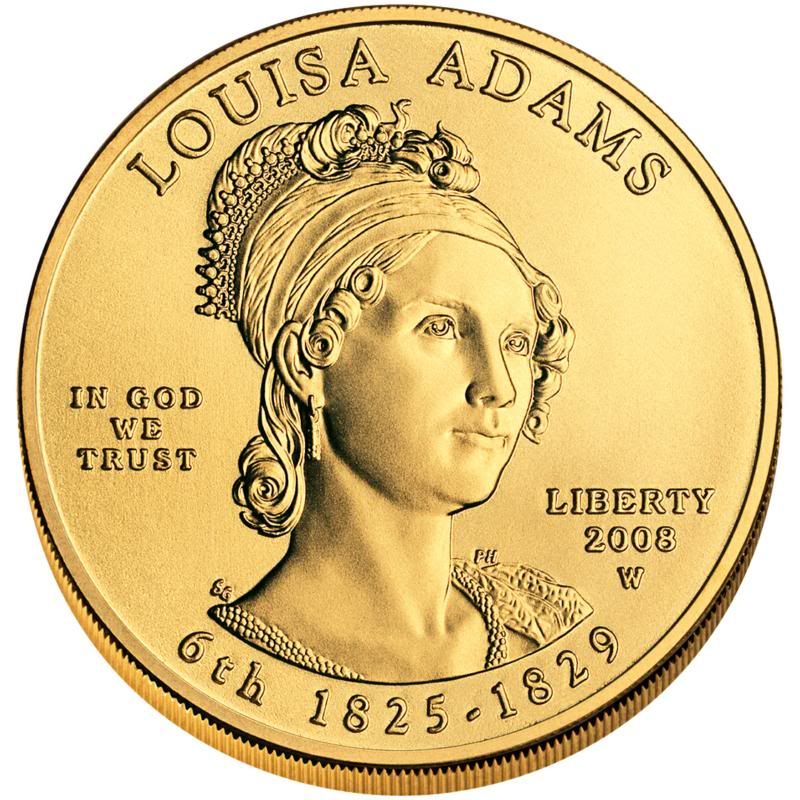

I support $1 coins, incidentally.

There’s been a debate going on amongst some of my fellow writers, and it’s past time I put in my two cents on the subject. Before I get to my thoughts on the matter, though, I highly recommend you do two things.

First, go on over to Terribleminds’ “The Care And Feeding Of Your Favorite Authors” and follow the instructions encased therein. Don’t worry, it just involves reading a few posts, nothing involving shotguns or whiskey or hobos or 4 D-cell powered vibrators.

Second, read this Mess Of Free Words On The Whole 99 Cent Thing on Going Ballistic. Come on back here when you’re done.

Lots of good stuff, there. I especially like Cat’s point that folks willing to spend $5.99 on a latte should be okay spending it on a book (just in case you missed it in Chuck’s post). And an anthology of short fiction shouldn’t differ in price too much from a novel; it can be just as tough to write one coherent 80,000 word narrative as it can be to write 8 10,000 shorts. Still, I have to admit I’m in agreement with most of my peers: $0.99 is too little for full-length fiction.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand the economical reasoning for wanting to spend less for more. Me and my ilk are not called starving artists because we’re flush with disposable income. So any opportunity we have to keep from going under while drawing in entertainment to help maintain our sanity is a good one. That doesn’t necessarily mean that dollar book on the e-store is a decent read, however.

The few e-books I’ve picked up for that low a price have been promotional or sale items from known quantities. Chuck and Seth Godin have established reputations, at least in the circles I travel through. It’s the unknown that makes me leery, the as-yet-unpublished authors tossing full-length novels on the Kindle store for less than a dollar with one five-star review from their mothers. I know this might seem like a nasty, negative attitude to have towards my fellow burgeoning bards, but the fact of the matter is my time is as precious as my money, and there’s only slightly more time than money for me to spread around. I’d like to avoid wasting it, if I can, which means being discerning about what and when I read.

It’s one thing to undercut the competition, like the big-name publishing houses asking $13 for the e-book version of a $12.99 hardcover when the $6,99 paperback is about to be released. It’s another to do it to the degree of seeming desperate. You have to sell your work, sure, but you don’t want to sell yourself short.

Self-publication on the electronic market seems more and more like the business model of freelancing in general. You won’t be charging as much as the big guys, but you need to be realistic in just how little you can charge. In order to earn, you need to set both your price points and end-user expectations appropriately. You want people to feel like they’ve made a worthy investment, that the services or entertainment they’ve paid for was worth the money. At the same time, we want to be paid what we’re worth and keep ourselves fed to do more work and, you know, keep on living.

It really boils down to a matter beyond market research and profit analysis, to one of personal confidence: How much to you stand behind your work? How much would you expect to pay for something similar? How willing are you to market it, to get out there and sell it? What are you offering that nobody else on the Kindle store can, and how much do people need it even if they don’t know they do until they see your listing?

I don’t think e-books are going to replace the real thing any time soon, and I’m going to continue to pursue many ways of getting my words in front of fresh new eyeballs. This might be another way of doing it, but I’d like to try and do it right, without selling myself short in the process.