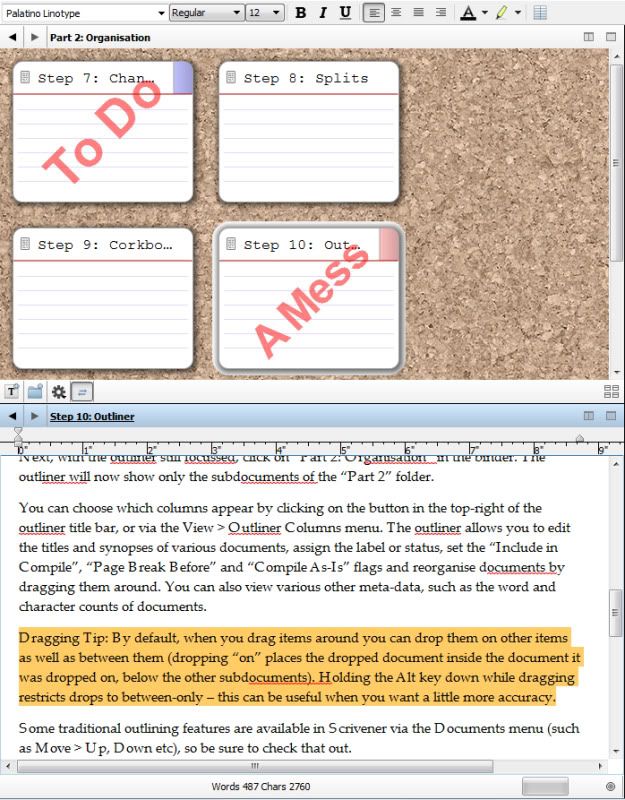

This is related to a post I made a few months ago regarding expository writing but it’s on my mind since my wife and I just finished watching (or rather re-watching) the Lord of the Rings trilogy. I’d borrowed the extended editions from my mother, as my copies are elsewhere.

Anyway, this if Faramir. In the books, he’s markedly different from his brother, Boromir, in that he does not fall into the sway of the One Ring. Throughout the narrative, he remains completely uncorrupted, unlike most other characters who encounter the ring. Even Galadriel, one of the oldest, fairest and most powerful elves in all of Middle-Earth, is tempted by this prize, but Faramir says he wouldn’t take it even if he found it on the side of the road.

In the films, Faramir is briefly tempted. He gets as far as Osgiliath with the hobbits, but Sam breaking the truth to the Gondorian about how his big brother died coupled with watching Frodo very nearly get scooped up by a Nazgûl shakes him out of it and moves him closer to the original text. Not enough for some fans, mind you, but you can’t please everybody.

Similarly, Aragorn doesn’t jump at the chance to become king in the movie. Instead of carting around Narsil in his back pocket waiting for the time to be right to reforge that sucker, in the films he shrinks back from the prospect of being king. He knows his family has a history of corruption and failure, having declined ever since the heroic death of Elendil and the utter undoing of Isildur because of the Ring. It’s only after many trials, many adventures, brushes with death and nearly losing the love of his life that Aragorn steps up and takes the noble legacy that’s been waiting for him all along.

As much as I’m a fan of the books, I like these takes on these characters a lot more. It shows growth, the development of the characters from an origin point to a final destiny. Aragorn doesn’t kick around in the North as Strider just to hide from Sauron as he does in the books; he also does it to hide from his own destiny, and the corruption he feels has eaten away at his lineage. Faramir’s line of not using the Ring even if he alone could save Gondor carries far more weight after his experiences with the Hobbits. It might not have been exactly what Tolkien intended, but along with expository writing, the man seemed to like birthing characters fully-formed from his mind.

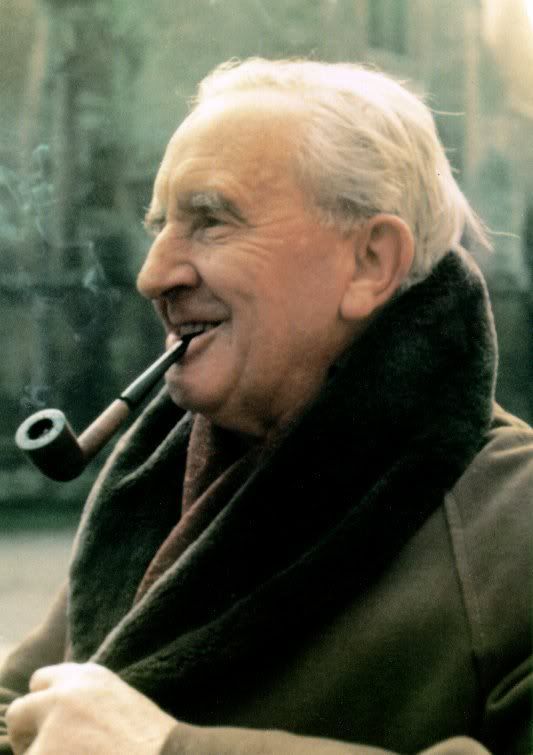

Let me reiterate that this man’s brilliant. He builds fantastic worlds with rich history and it’s something that gives his narrative weight. But there are two things in his works that bother me a bit as a writer. In addition to the aforementioned exposition, a few of his characters don’t develop a great deal. They’re not grown through their experiences as the story unfolds, they simply are whatever Tolkien needs them to be.

It’s not true for all of his characters, certainly. Both Bilbo and Frodo are very different Hobbits from when they start out in the beginning of The Fellowship of the Ring. Even moreso, Bilbo changes because of his experiences in The Hobbit and when we catch up with him on his 111th birthday, he’s no longer the respectable bachelor of Bag End, but seen as something of a recluse and troublemaker. Given, these are the main protagonists of two narratives we’re talking about, while Aragorn and Faramir are somewhat less prominent. They’re no less important, however, given the structure and flow of the story.

While not every character in a story necessarily has to become changed by the events that unfold, the characters that directly impact those events should be cultivated in such a way that they do change. Otherwise, they quickly become static, even boring. I’d like to think that, in the way that Aragorn and Faramir were cultivated in the films to show their nobility and generosity of spirit through action and circumstance rather than telling us how noble they are, Tolkien would have approved.